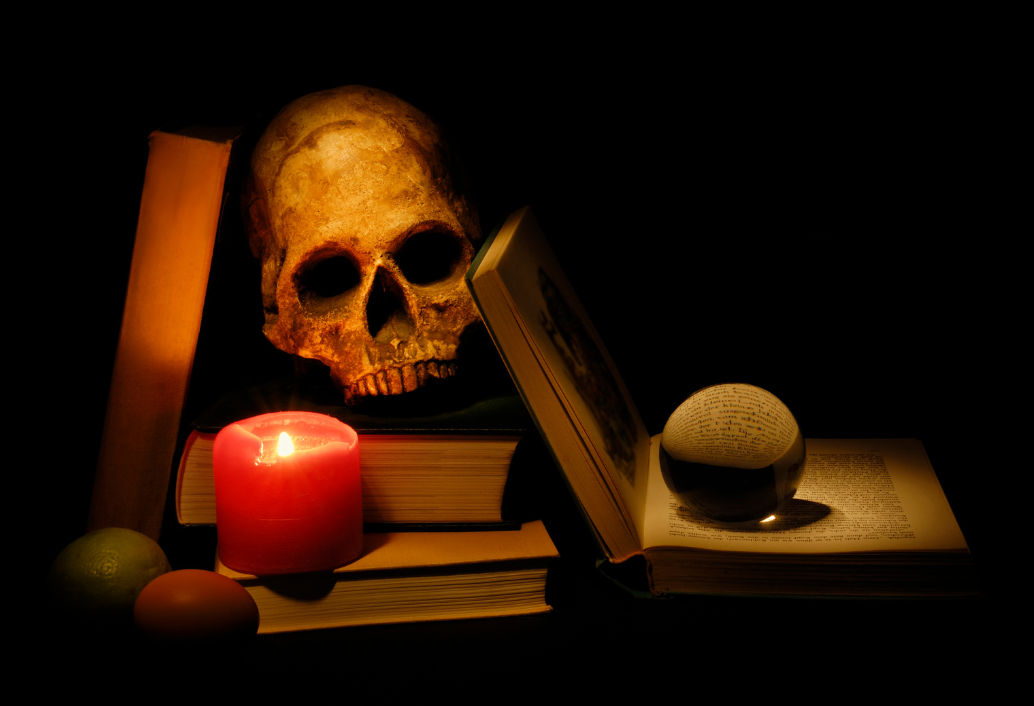

Dark Nights, Dead Bodies and Dusty Law Books

Kurt X. Metzmeier

Although October gets a lot of attention, November may be the true start of the spooky season. The sun sets early and the harvest days known to the Anglo Saxons as Blōtmōnaþ,” or Blood-Month, began with two Christian holidays devoted to death and remembrance, All Saints Day (November 1), which hallowed martyrs of the church, and All Souls Day (November 2) when the family of the deceased were encouraged to pray for the souls of their ancestors and maybe advance their way through the shadowy mists of purgatory.

In the more enlightened days of 19th century Kentucky, it was around this time of year that the body snatchers of old came out, using the darkness of November to dig up cadavers for the start of anatomy classes at medical schools like that of the University of Louisville, which was founded in 1837 at a time when bloodletting was still an acceptable medical treatment.

To explore the law governing these ghoulish deeds, it is perhaps appropriate to turn to the “walking dead” of the legal research field: dusty legal encyclopedias, worn old digests of law, age-stained Kentucky statute books and the inscrutable volumes of the American Law Reports, or ALR, which aren’t law reports at all.

Common Law and Common Graves

In the 1830s the rising river city of Louisville began to create the institutions of a proper city. The University of Louisville School of Medicine was one of them, founded by faculty from Transylvania University’s medical department. The Kentucky Encyclopedia suggests that one incentive was that the well-populated city would have better access to cadavers for classroom dissections than Lexington. And that was likely true. Drawing on the papers of the Filson Society, Heather Fox writes in the 2008 Filson magazine about a memoir by one former student, Louis Frank, who tells of a long wagon ride from the medical school on Chestnut Street to a paupers’ graveyard on Manslick Road. This midnight excursion by Frank and a fellow student to rural Jefferson County was to secure a corpse required for class. The account reveals a few scares—including a brief police stop where the graverobbers had to pass off the cadaver as a sleeping companion.

If such an encounter had happened early enough, there would have been little to fear. The common law of England had long ago determined that a dead body was not property and thus could not be stolen. (Their clothing was property, so bodies “harvested” for the medical schools were carefully undressed). While grave robbers didn’t fear the law, the well-armed families of the deceased did pose a worry—which is why a pauper’s grave was the target of Dr. Frank’s midnight ride, not a fancy cemetery like Cave Hill. Of course, the common law can be modified by positive law like a statute, and eventually, Kentucky families demanded a law to protect their loved one’s gravesites.

The Living Dead: Books

When one is researching the law of graverobbing, it seems appropriate to start with the books. While many of the resources I discuss below can be found online, I’m frankly a little nervous about alerting the algorithms of Westlaw and Lexis to my seemingly newfound interest in dead bodies. Besides, how can I resist when the spine of volume 22A of American Jurisprudence 2d beckons “DEAD BODIES TO DECLARATORY JUDGMENTS”?

In general, a legal encyclopedia is a good starting place whenever one wants to research a legal area new to them. “Dead Bodies” begins with an outline of the article that serves as an outline of the topic. Each issue is discussed concisely, with citations to leading cases for almost every sentence. The article references related American Jurisprudence or “AmJur” entries, the West Digest and key numbers related to the subject, and citations to useful ALR articles (more about this later). As much as I’d like to read nothing but gruesome old cases, the entry is being written for modern lawyers and thus it is relentlessly up to date. However, § 3 does note some of the history of the common law of grave-robbing and early statutes.

Another legal resource with a long history is the ALR, now in its seventh edition. (Like people use KFC for “Kentucky Fried Chicken,” no one ever says “American Law Reports”). Describing the ALR is challenging because it started out as a reporter of interesting cases, each paired with an article called an “annotation” that placed the case in context. Soon the annotation was the star, each discussing a very specific legal concept in great detail, with citations from as many jurisdictions as warranted. Following a ALR reference I found in AmJur, I find Construction and Application of Graverobbing Statutes, 52 A.L.R.3d 701 (1973). It collects a crypt full of legal precedents on graverobbing, with sections on all the more relevant issues and citations to leading cases around the country.

I go next to the first edition of the Kentucky Digest. Although there is a second edition, it only collects cases from 1930, while the first goes back to Kentucky’s founding in 1792. The West Digest and key numbers that I retrieved from AmJur, take me right to all the “headnotes” (short, one-paragraph case summaries) related to Dead Bodies as a subject of crimes and torts. There are a few interesting cases, and one directs me to Kentucky’s earliest graverobbing statute.

In the Revised Statutes of Kentucky of 1852, under the heading Crimes and Punishments, section 15, the statute law first decreed that “Whoever shall unlawfully or secretly disinter or disinterring bodies displace any dead human body from the grave or vault in which it has been deposited, shall be fined not more than five hundred dollars, and imprisoned not exceeding six months, or both, at the discretion of the jury.” While this did not stop graverobbing, it was now formally a crime. Old statutory codes like this—Kentucky’s first legislative revision—can be found in the UofL Law Library’s Attic. (If that is too creepy, we also have them in our HeinOnline database).

Some Interesting Cases

Along the research trail, a few interesting cases arose. One case, Meyers v. Clarke, 90 S.W. 1049 (Ky. 1906) found that doctors could be found liable in tort law for what the court delicately called an “unauthorized autopsy.” A few cases noted that cadavers being transported were not property even when the negligence of a railroad caused “the dead body of a relative being thrown from a wagon” the family could not recover. Hockenhammer v. Lexington & E. Ry. Co., 74 S.W. 222 (Ky., 1903).

The ALR annotation has an interesting Kentucky reference although not on graverobbing per se. In City of Louisville v. Nevin, 73 Ky. 549 (Ky. 1875), a holder of a lien on a Roman Catholic graveyard filled with graves wanted to force its sale because the trustee-owner was insolvent. The chancery court refused to order the sale on the theory that the land was useless as any purchaser could make no use of it without violating the statute punishing the desecration of graves. The Court of Appeals rightly upheld this ruling. Since bankrupt cemetery corporations still are with us—one need only look at Eastern Cemetery in the Highlands, Greenwood Cemetery in the West End, and Schardein Cemetery near Shively—letting a single creditor force the sale of a packed graveyard would cause a manifest injustice.

Conclusion

From reading the Kentucky cases and statutes, it becomes apparent that despite a focus on the horror movie ghouls who robbed graves for medical dissection, the statutes protecting against disturbing the dead have been most usefully employed against property developers seeking to clear land to build on. (Judges apparently value well-trained doctors to keep them personally alive over the peaceful repose of one dead person.) The paupers’ graveyards and rural cemeteries of one century inevitably become the prime real estate of another. And without such laws, it’s cheaper to just bulldoze them under and build nice suburban homes on them. Hmm. I think I’ve seen that horror movie.

Kurt X. Metzmeier is the interim director of the law library and professor of legal bibliography at the University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law. He is the author of Writing the Legal Record: Law Reporters in Nineteenth-Century Kentucky, a group biography of Kentucky’s earliest law reporters, who were leading members of antebellum Kentucky’s legal and political worlds.